Since the Legal Services Board published our report on the Cab Rank Rule on 22 January we've had many comments coming in on the discussion boards. They are not all negative, though many are.

I wanted to give some of the flavour of what is coming our way. We expected it of course. The first article to appear was in the Law Society Gazette (the solicitors' journal not barristers') which has garnered many comments. I have tried replying to a few. Catherine Baksi gave a good summary of the papers. Here are some of the comments:

The latest idiocy

Submitted by Interested observer on Tue, 22/01/2013 - 15:01.

The fact that a fundamental principle is not understood by the market place is no reason for abolishing it.

This is a sensible step

Submitted by Disinterested observer on Tue, 22/01/2013 - 15:07.

This is a sensible step forward. Most other countries do not have this silly rule. Indeed, some other countries view this rule as entirely unethical. This will level the playing field and allow people to receive better representation, and allow lawyers to openly restrict themselves to cases they actually take.

There is no point in having a rule that is not enforced, unenforceable and not generally supported merely because a minority does.

And what is to happen the

Submitted by Andrew on Tue, 22/01/2013 - 16:18.

And what is to happen the first time a Defendant accused of some really nasty offence - Huntley, or the man who killed Millie Dowler - cannot find representation because every lawyer approached reckons it will cost more work than it is worth?

The defendants accused of

Submitted by Anonymous on Tue, 22/01/2013 - 16:34.

The defendants accused of really nasty offences that are media worthy will not have a problem getting representation because that is exactly the kind of high-level exposure that criminal barristers want. Such exposure is not only fun to have, but also increases business.

Working around the Cab Rank

Submitted by Tim Child on Tue, 22/01/2013 - 17:27.

I have never had a barrister outright refuse a case, and as a matter of principle I would only ever send instructions/brief to a barrister who I would expect to take the case unless given very specific instructions by my client as to who he/she/it wishes to use.

I have, however, had an experience where the fee demanded by my client's chosen barrister was deliberately priced so high that my client couldn't possibly afford it. The clerk was absolutely open about it - saying that this eminent barrister regularly advised the other party to the dispute and, while on this occasion there was as yet no conflict, he would need a substantial fee to justify subsequently having to turn away the other work that he expected to be offered.

In other words, not quite "No thanks, don't fancy your client.", but as near as dammit.

Modern academia

Submitted by faithless on Wed, 23/01/2013 - 09:29.

Yes, this is what we expect from the half-educated half-wits who become professors nowadays. "The rule is imperfect, so it must obviously be abolished."

Might as well abandon the whole of criminal law, then, since that doesn't punish let alone convict a significant proportion of perpetrators.

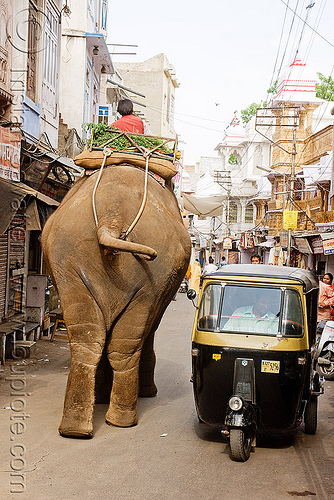

What might happen if the rule was abolished altogether has been recently illustrated in India, where the Bar has rushed to announce that it will have nothing to do with defending those beyond-the-pale men charged with the rape and murder of the student on the bus. After all, why imperil your career or endanger your family for fear of reprisals against your representation of such obviously unworthy objects of legal attention?

Since then we had an article by the "Chief Officers' Network" which concluded,

So, there it is, then. More jobs for the boys: a consultation that means that there will be more time and money spent.

So let's save both: listen very carefully.

THE CAB RANK RULE DOES NOT WORK. IT HAS NOT WORKED FOR AT LEAST 25 YEARS. SCRAP IT. AND DON'T SPEND A FORTUNE DECIDING WHETHER TO REPLACE IT AND IF SO WITH WHAT. IT'S A FREE MARKET, IT OPERATES LIKE A FREE MARKET AND HAS DONE SO WITH SUCCESS FOR A LONG TIME. REMOVE THE FAKE RESPECTABILITY AND LEAVE IT ALONE.

And next time you want a proper opinion, ask a lawyer. Hell, ask me: I'll do it in a fraction of the time, for a fraction of the cost.

One of the best write ups came from Dan Bindman at Legal Futures. No comments there but it had been tweeted extensively.

We've thrown the stone in the pond, let's see where the ripples end up. The Bar has begun but as the Law Gazette said,

We've thrown the stone in the pond, let's see where the ripples end up. The Bar has begun but as the Law Gazette said,

Chair of the Bar Standards Board Baroness Ruth Deech said: ‘We will analyse the report with interest but we are clear that removing this fundamental principle would send out a dangerous message.

‘The cab rank rule protects barristers who take unpopular causes and reassures the public that they are entitled to representation even if their case is controversial in nature.

‘The rule has served the public and the standing of British law well for centuries we have no evidence that it does any harm.’